It seems bizarre to imagine a time when college sports did not include Black athletes. In my lifetime, I cannot remember a time when my team, the Oklahoma Sooners, did not have significant football players who were Black.

It seems bizarre to imagine a time when college sports did not include Black athletes. In my lifetime, I cannot remember a time when my team, the Oklahoma Sooners, did not have significant football players who were Black.The first I remember as a young fan was the outstanding nose guard, Granville Liggins, who starred in the 1968 Orange Bowl victory over Tennessee – the first television broadcast of an OU game that I can remember watching.

(At the time Tennessee had not integrated its football team. Their first Black football player came a year after the Vols lost that night to Liggins and the Sooners 26-24. I did not realize OU was playing against an all-white team when I watched the game in our living room. I don’t believe I, at age 9, knew the significance of that).

And then there was Eddie Hinton, the Black star wide receiver, who I followed with great interest as he went on to the NFL; and then later, of course, there was Greg Pruitt, who in my view is the football player who changed the run game from brute strength to blazing speed.

And of course there were the heralded Selmon brothers, whose soft spoken friendly demeanor off the field would give way to Godzilla-like physical dominance and devastation in their defensive line positions on the field. No doubt the Selmons played a gigantic role in Oklahoma football’s winning tradition; but, also, they had important positive impact on how white football fans viewed Black players at a time when some fans remained hostile to young Black men.

It is easy for any intellectual analysis of race relations in America today to dismiss the role sports has played in our racial history. One could contend Black youngsters have been used as the sports gladiators for white folk entertainment.

And, certainly, the motivation of Oklahoma coaches Chuck Fairbanks and Barry Switzer (and Coach Wilkinson before them, with the addition of Prentice Gautt to the Sooners team in 1956 as one of the first Black players in the country to play major college sports) may not have been to make some social statement about equality and diversity. They just wanted to put the best players on the field and this led to integration of their teams.

It was an example of how holding onto old traditions, which included racial discrimination, was not a good thing for anyone. The deleterious effects were not limited to Black people. The benefits of removing institutional racial prejudices in our society benefit white people too.

The message of the Game of the Century to the college football world: Bringing diversity to the football field was going to happen. At least if you wanted to win.

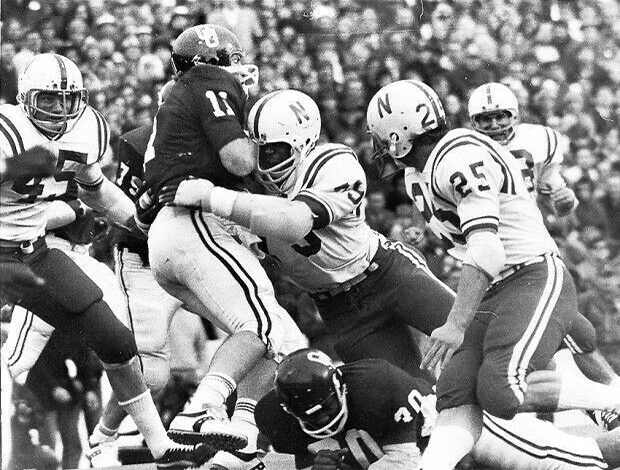

When Nebraska brought its No. 1 defense to Norman in 1971 it faced the No. 1 offense in the Oklahoma Sooners. The stars of those teams were Nebraska noseguard Rich Glover and Oklahoma running back Greg Pruitt. Nebraska RB Johnny Rodgers. Oklahoma’s Lucious Selmon. Black athletes. On the biggest stage in the biggest game of the year. The biggest game of the Century.

In the 1970s the ugly forces of prejudice and bigotry existed in Oklahoma. But, the overwhelming desire to win became intertwined with allowing Black athletes to be judged not by the color of their skin, but their athletic prowess. And the consequence was equality in the football program. And great success for Oklahoma’s program, for which many white folks like me were delighted.

By contrast, as an AP article this week recalled, all this was slow to come in the South, in places like Alabama. And also in Texas.

The Game of the Century on national television was an announcement to those other schools that times were changing. The message of the Game of the Century to the college football world: Bringing diversity to the football field was going to happen. At least if you wanted to win.

When Nebraska and Oklahoma take the field on Saturday and commemorate the 1971 Game of the Century, we fans will see it as commemoration of our youth, and the effect that particular game had on shaping our view of our fandom relationship with our teams — recalling how we were crouched in front of the TV, holding our breath as the key plays were about to occur, spellbound by the BIG plays made by these amazing athletes wearing our colors.

Those are experiences we’ve had many times since, but for many of us, those all began that day when these teams went at it in November 1971 on Owen Field.

But, we can also watch this game on Saturday as tribute to a time in college sports when the landscape changed. And for the better. When it changed to allow young Black athletes to see a future instead of a wall.

Follow

Follow